50 years after fall of Saigon, Vietnam can’t heal by erasing half its past

Nghia M. Vo

Opinion contributor

History is not just about remembering victories. For reconciliation to happen, the Hanoi government must stop discriminating against those who fought for South Vietnam.

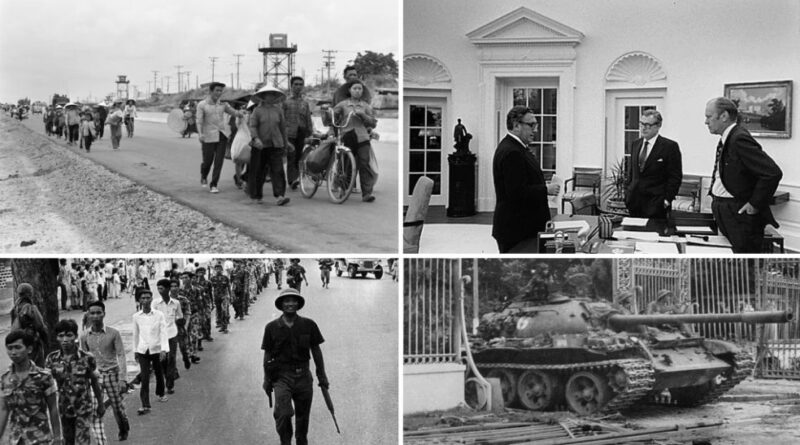

April marks 50 years since the fall of Saigon, and the wounds of the Vietnam War remain open ‒ not just for Americans who fought there, but also for those who lost everything when the war ended in the death of South Vietnam.

For those who fought alongside the United States, the past five decades have been defined by discrimination and erasure under Vietnam’s communist regime. They are not honored as veterans but treated as traitors or U.S. puppets.

History is written by the victors, but a nation cannot truly heal by erasing half of its past. For reconciliation to happen, the Vietnamese government must acknowledge the suffering of those who had fought for South Vietnam ‒ not as enemies, but as fellow citizens.

‘Internal hemorrhaging of modern Vietnam’

The fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, ended the Vietnam War.

While North Vietnamese veterans are celebrated, their southern counterparts ‒ as many as 400,000 officials and officers spent years in reeducation camps ‒ have been denied benefits, government jobs and basic dignity. Hundreds of thousands others were sent to “new economic zones,” the civilian equivalent of the reeducation camps. About 2 million people fled as boat people ‒ of which more than 500,000 died or disappeared.

Historian Christopher Goscha suggests that “this internal hemorrhaging of modern Vietnam was proof that national reconciliation had been a failure.”

Private and business properties, lands and bank accounts were confiscated. Memorial sites were demolished, cemeteries desecrated, musical records and cultural artifacts destroyed, and agriculture was collectivized leading to a decade of famine into the 1980s.

In a poor country where the haves and have nots once coexisted, the new Socialist Republic of Vietnam proudly exhibited a uniformly poor populace, with the newest poor being the citizens of the former South Vietnam.

For former South Vietnamese veterans, war has never ended

After Saigon fell, the 130,000 distraught and dispossessed who evacuated landed on foreign soils. Other waves of refugees joined them, swelling the size of Vietnamese enclaves worldwide. They worked hard and took one or more menial jobs to slowly climb social ladders. They sent money back home to help impoverished relatives.

The Vietnamese refugees fought for the preservation of their culture and the commemoration of the fall of Saigon as well as the loss of those who died fighting for freedom. Now, community memorials in America acknowledge and reinstate the presence of the South Vietnamese into the Vietnam War.

The South Vietnamese who fled to the United States have thrived, building successful businesses, contributing to academia and preserving their heritage in ways that would have been impossible under the communist Vietnamese regime. Their success is proof that their belief in democracy and free enterprise was not misplaced. But for those who remained in Vietnam, the war has never truly ended.

The Hanoi government has never been serious about reconciliation as South Vietnamese veterans languished as second-class citizens without job support, economic and social help. Even today, efforts to support these forgotten veterans are blocked.

Reconciliation is a word spoken in theory but not practiced in reality.

The U.S. failure in Vietnam in 1975 ‒ and in Afghanistan in 2021 ‒ proved that military strength alone cannot win wars of insurgency. Firepower can topple governments, but it cannot build stable societies. America’s mistake was believing that it could impose stability through force, without the long-term investment needed to rebuild shattered nations.

As we reflect on the 50th anniversary of the war’s end, the United States should recognize and support those South Vietnamese veterans who remain marginalized in their birthplace. These men risked everything to fight alongside U.S. soldiers. They deserve recognition, not abandonment. The government of Hanoi should also stop discriminating against these veterans.

History is not just about remembering victories. It’s about acknowledging the costs of war, the lives forever altered ‒ and the people still waiting for justice.

Nghia M. Vo is a retired physician, independent researcher, and author specializing in Vietnamese history and culture. His books include “The Vietnamese Boat People, 1954 and 1975-1992,” “Saigon: A History” and “My Vietnam, Your Vietnam.” He lives in Virginia. (USAToday)