On the Anniversary of the Fall of Saigon, Beware of the Desire to Save Face at All Costs

Jonah Shrock (HKS)

April 30, 2025

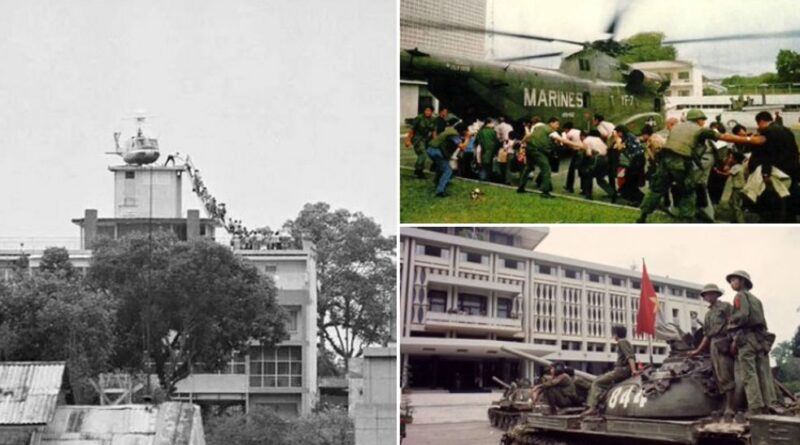

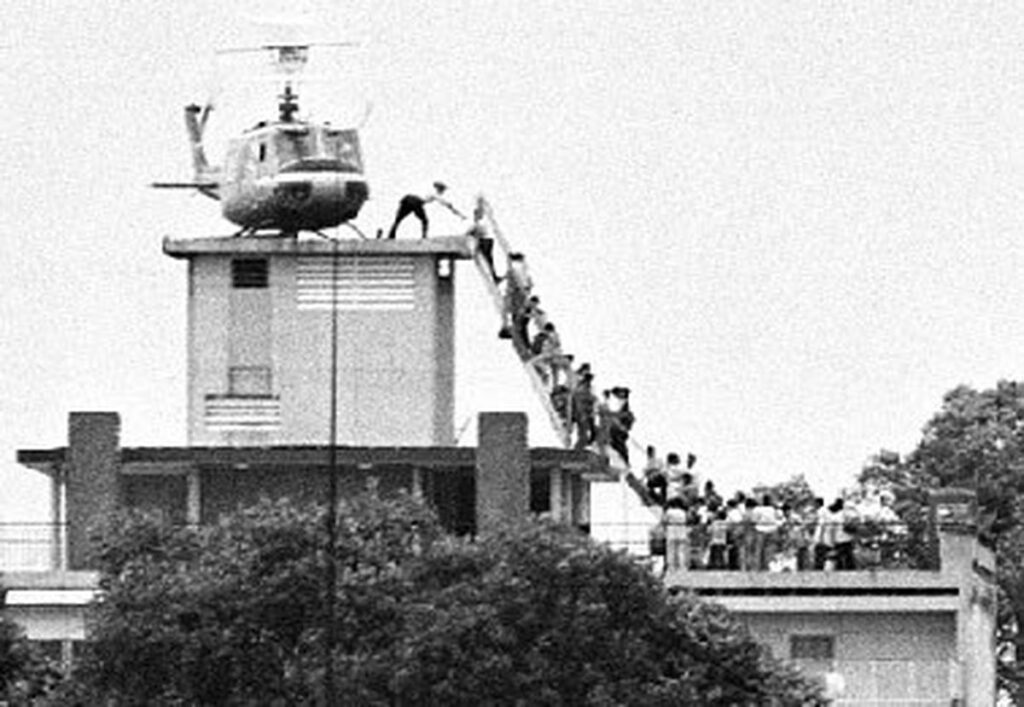

Fifty years ago today, Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese, officially rendering the United States’ decades-long misadventure in Vietnam a failure.[i] The troubling reality of wartime decision-making is that it was not based primarily on whether the United States could feasibly win, or even whether Vietnam was strategically important. Rather, policymakers in Washington escalated the conflict largely on the basis that failure would impact America’s reputation and thus its credibility. If the United States gave up, other powers would question our resolve.

Much to America’s detriment, this logic has persisted since. Since Vietnam, we’ve seen other examples of what president Obama referred to as “Dropping bombs on someone to prove that you’re willing to drop bombs on someone.”[ii] As we head deeper into the Trump presidency, the anniversary of the Fall of Saigon is a reminder that America’s reputation may not be as important or as easy to control as many think, and obsession over it leads U.S. foreign policy astray.

In a February 1965 memo to President Johnson, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy wrote that “American responsibility is a fact of life which is palpable in the atmosphere of Asia, and even elsewhere. The international prestige of the United States…[is] directly at risk in Vietnam.”[iii] In other words, the world knows America has made pledges to support South Vietnam, so if it backs out, it will look bad.

Yet Bundy harbored doubts about the war’s winnability. Just four months later, Bundy wrote that “if and when we wish to shift our course and cut our losses, we should do so because of a finding that the Vietnamese themselves are not meeting their obligations.”[iv] Already in June 1965, he had resigned to the fact that the war could not be won. As such, he figured, we had better make it look like it was the fault of the Southern Vietnamese and not of the United States. Saving face was the priority.

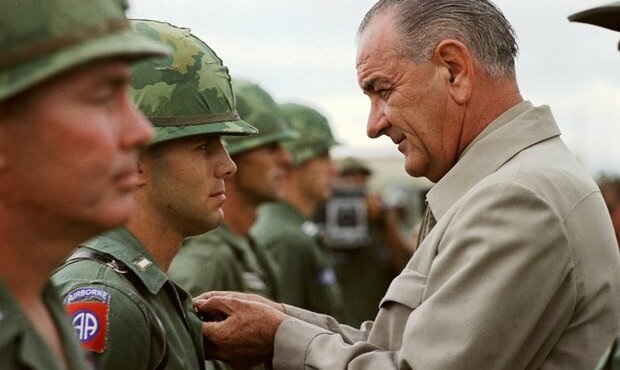

From the early days of his administration, President Lyndon B. Johnson was also skeptical that Vietnam could be won or that it mattered to U.S. security.[v] Shortly before the first ground troops landed in Vietnam, he told Senator Richard Russell “There ain’t no daylight in Vietnam. There’s not a bit.”[vi] Yet the same year as this comment and Bundy’s memo, Johnson was publicly making the case for escalation.

According to Johnson, America’s active demonstration of following through on its commitment is important because it influences the decisions of allies and foes. In an address at Johns Hopkins University in April 1965, Johnson said withdrawal would shake confidence in “the value of American commitment and the value of America’s word.”[vii] He told audience that if America retreated from Vietnam, other communists would be emboldened and ”The battle would be renewed in one country and then another,” essentially an articulation of Domino Theory. The logic is deceptively simple: If we break our promise, no one will believe us in the future.

It was on this basis that the United States escalated the war. Between 1965 and U.S. withdrawal eight years later, well over a million lives would be lost. In hindsight, we know this effort would fail and Saigon would fall 10 destructive years later. But was continuing a war, mostly in the name of preserving the United States’ reputation a valid purpose in the first place?

Many international security scholars who study credibility would say “no”. [viii]Dartmouth political scientist Darryl Press analyzed the decision-making processes of leaders responding to adversaries’ threats. He found that an adversary’s history of breaking or keeping promises did not affect leaders’ calculations.[ix]

Rather, what matters are power and interests. Does my adversary have the power to carry out this threat at the present moment? And would it be in its interest to do so? If the answer to both of those questions is yes, the threat will be taken seriously even if the adversary has a history of breaking promises. This remains true even if this history is recent and the same leader is in power.

Digging deeper into the oft-cited example of the lead-up to World War II, Press found that even though the United Kingdom and France had failed to check Nazi Germany in the past, “German leaders almost never discussed past British and French irresolution when they debated foreign policy alternatives.”[x] Allowing Hitler to conquer the Anschluss and the Sudetenland was an error not because it affected Allied credibility, but because it allowed the balance of power to shift in Germany’s favor.

There is also evidence that past actions do not have much effect on the credibility of alliances. During this period, Mussolini reneged on his commitment to help Hitler fight in Czechoslovakia and Poland. Nonetheless, when Hitler was making plans to take France, he assumed Mussolini would support him by engaging French troops on the border with Italy. Reputations did not drive Nazi assessments—power and interests did.[xi]

Not all political scientists agree with this analysis. Frank P. Harvey and John Mitton, for example, have written a book refuting Darry Press’ arguments.[xii] Others, like Keren Yarhi-Milo Dean of Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, present a convincing middle ground. All else equal, reputation can have an impact on credibility, but how a reputation is created is difficult to understand and hard for policymakers to control. For example, she and Alex Weisiger found, backing down from a crisis can make a country more vulnerable to a challenge the following year, though causality is difficult to prove. [xiii] She also has research demonstrating that biases affect leaders’ perceptions of other powers’ decisions. So, a reputation can matter in certain situations, especially when power and interests are unclear. But ultimately, it is extremely difficult to know exactly what reputation your actions are creating.

Vietnam is the perfect encapsulation of this phenomenon. A war whose logic fixated on reputation for resolve may have done the opposite by making future U.S. leaders more wary of bogging the United States down abroad. Even if policymakers like Bundy were right that reputation matters in establishing credibility the desire to protect the United States’ reputation—and to avoid the embarrassment of a withdrawal—led each successive administration to delay the inevitable. The paradox lay in the fact that as the war dragged on and victory seemed ever more elusive, the political cost of withdrawal increased, making it harder for any president to accept failure. If withdrawing after five years looks bad, doing so after a decade looks even worse. And no president wanted to be known as the president who finally lost Vietnam.

Yet despite this evidence and the catastrophic failure of Vietnam, we never learned our lesson. In every debate over foreign policy, American policymakers reliably justify escalation and continued entrenchment abroad with concerns over American credibility.

This same destructive logic played out again in Afghanistan. After initially driving the Taliban from power, America ended up bogged down in a Vietnam-like quagmire that would break the record for our longest war.[xiv] Time and again, calls to cut our losses were rebuffed by fears over the damage it would do to America’s credibility. Again, the political dynamic persisted—there was little political cost to leaving troops in the country for a few more years, whereas the blowback for the decision to withdraw could be massive. Biden recognized that delaying the inevitable any further only prolonged the costs. Yes, the pullout was executed horrendously. But he deserves credit for having the political courage to end a war that ultimately was not in America’s interest to continue.

After the withdrawal, Washington abounded with think tank roundtables about how it would affect our credibility. Some warned allies would no longer trust the U.S. I see little evidence of this. If anything, it was the quixotic pursuit of an unachievable goal in Afghanistan for too long that called into question America’s dependability.

President Trump’s erratic foreign policy proposals—from seizing the Panama Canal to annexing Greenland—could present similar traps. Taking Canada as America’s “51st State” by force, for example, could create the need for prolonged counterinsurgency operations, as Canadians likely won’t take kindly to being invaded.[xv] Though unlikely, other countries could come to Canada’s defense, enlarging the conflict. Policymakers would likely eventually realize that the old status quo of a peaceful border and robust economic relations with our neighbor to the north was far preferable. Yet in response to calls to abandon our initial goal, there are inevitably protestations that backing down hurts our credibility. Though enticing, history makes clear that chasing credibility at all costs is a path to disaster.

U.S. credibility does not hinge on never withdrawing from doomed wars—it depends on making clear, limited commitments tied to genuine strategic interests. That, not blind perseverance, will make America credible. (HKS)

Jonah Shrock, “On the Anniversary of the Fall of Saigon, Beware of the Desire to Save Face at All Costs”, The HKS Student Policy Review, 30/04/2025

[i] I would like to thank Fredrik Logevall, Nancy Gibbs, and Stephen Kinzer for their feedback on this article.

[ii] Keren Yarhi-Milo, “The Credibility Trap,” Foreign Affairs, June 18, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/credibility-trap-reputation-yarhi-milo.

[iii] Mark Atwood Lawrence, The Vietnam War: An International History in Documents, Illustrated edition (New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[iv] McGeorge Bundy, “24. Memorandum From the President’s Special Assistant for National Security Affairs (Bundy) to President Johnson,” State Department – Office of the Historian, June 27, 1965, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v03/d24.

[v] As historian Fredrik Logevall has written ” Publicly, Johnson projected optimism. But the truth is that he was always a bleak skeptic on Vietnam — skeptical that it could be won, even with American air power and ground troops, especially in view of the weaknesses of the South Vietnamese military and government, and skeptical that the outcome truly mattered to American and Western security.” See: Fredrik Logevall, “Opinion | Why Lyndon Johnson Dropped Out,” The New York Times, March 24, 2018, sec. Opinion, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/24/opinion/lyndon-johnson-vietnam.html.

[vi] Fredrik Logevall, “Opinion | Why Lyndon Johnson Dropped Out,” The New York Times, March 24, 2018, sec. Opinion, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/24/opinion/lyndon-johnson-vietnam.html.

[vii] Lyndon Johnson, “Address at Johns Hopkins University: ‘Peace Without Conquest.,’” The American Presidency Project, April 7, 1965, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-johns-hopkins-university-peace-without-conquest.

[viii] Besides Darryl Press, other scholars who mostly support this view include Jonathan Mercer, Ted Hopf and Stephen Walt. See: “Roundtable 10-3 on Fighting for Credibility: U.S. Reputation and International Politics,” The Robert Jervis International Security Studies Forum, December 1, 2017, https://issforum.org/roundtables/10-3-credibility. ; Stephen M. Walt, “America Has an Unhealthy Obsession With Credibility,” Foreign Policy (blog), April 28, 2025, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/01/29/us-credibility-ukraine-russia-grand-strategy/.

[ix] Daryl Grayson Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats, Cornell Studies in Security Affairs (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2005).

[x] Press, 145.

[xi] Press, 46, 79.

[xii] Frank P. Harvey and John Mitton, Fighting for Credibility: US Reputation and International Politics, 1st edition (Toronto ; Buffalo ; London: University of Toronto Press, 2016).

[xiii] Keren Yarhi-Milo, “The Credibility Trap,” Foreign Affairs, June 18, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/credibility-trap-reputation-yarhi-milo.

[xiv] “America’s Longest War,” Foreign Affairs, May 14, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/anthologies/2021-05-14/americas-longest-war.

[xv] Donald J. Trump, “Good Luck to the Great People of Canada.,” Truth Social, April 28, 2025, https://truthsocial.com/@realDonaldTrump/114415618596069518.