How to Write an Ending to a Never-Ending War.

Andrew Lam

I once stood in front of a roomful of high school students and read a story about the end of the Vietnam War, and how I fled to America as a child, and how that experience continued to haunt and inform me, when a young woman, moved by my story, raised her hand. “Can you tell me why my father never told me about that war? He drinks a lot. But he says little.” Her father was a South Vietnamese soldier, she said, and he saw much bloodshed, but his sadness was mostly internalized, or else it expressed itself with bouts of rage.

“Sometimes the memories of the horror are too much to bear, and you can’t find the words,” I managed. “But even if never spoken or shared, trauma has a way to pass on. This is why we all need to find a way to confront and process that sadness. For me, it is through the act of writing.”

The young woman nodded, then she broke down and wept. Her friends rushed to comfort her. The room fell silent then but for the sounds of her weeping. It was as if in that moment it finally dawned on her that she was part of something much larger than herself, that the personal and historical are intrinsically bound—that the bombs that detonated on a distant land years ago somehow continue to reverberate in the heart of a girl born years later in America’s Midwest.

But such is war.

I watched her cry, and it reminded me of that famous James Baldwin quote: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.”

After my lecture, she came up and said she always wanted to write. And seeing me, the first Vietnamese writer she ever met, she felt now that she could.

At another lecture, some years later, a young man, also Vietnamese American, came up to thank me afterward. As a college student, he had attended one of my readings in the past and bought one of my books: Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora.

Apparently that book made an impact—so much so that he made his parents read it, too. It moved me that a second-generation Vietnamese American who didn’t speak Vietnamese and who knew little about the experiences of the boat people, that mass exodus of Vietnamese after the war, during which hundreds of thousands suffered murder, rape, storms, and drownings, told me my writing opened his parents up about their past.

“I asked them, ‘Why didn’t you tell me about how you escaped, or life in the refugee camps, and what it was like during the war?’ And they said, ‘Well, we didn’t want you to be haunted by our stories.’”

But he wanted to understand, he argued. He wanted to know what haunted them. “Your book gave them permission to tell their stories. So, they promised from now on they will tell me everything I wanted to know.”

I confess that the two episodes above were among the most powerful experiences I have had in my more than three decades as a writer. My own sadness, expressed through the written word, somehow connected one generation to another and bridged that yawning gap often made up of silence and hidden grief.

A refugee boy who grew up angry and confused in America, I was fragmented inside. Burdened by the memories of a war that I witnessed as an Army brat, I, who had come to America at a pubescent age, became an American so quickly that, after some years, it felt as if there were two versions of myself that were vying for attention; two distinct heartbeats.

After college, instead of going to medical school as my parents expected me to do, I decided to become a writer. I did it against my parents’ wishes and out of desperation. I never thought about the impact my written words might have on future generations. I simply wanted to connect my Vietnamese past to my American future. I wanted to be made whole again.

So, why do I tell you all of this? Because it is now 50 years since that war ended, and that refugee boy is now an American man steeped in middle age. And the best thing I can say about war, if you went through one and survived it, is that the horror and the hurt do fade with time, especially if you work through them. But by the same token, for those of us who were profoundly touched by war, it never, ever truly ends.

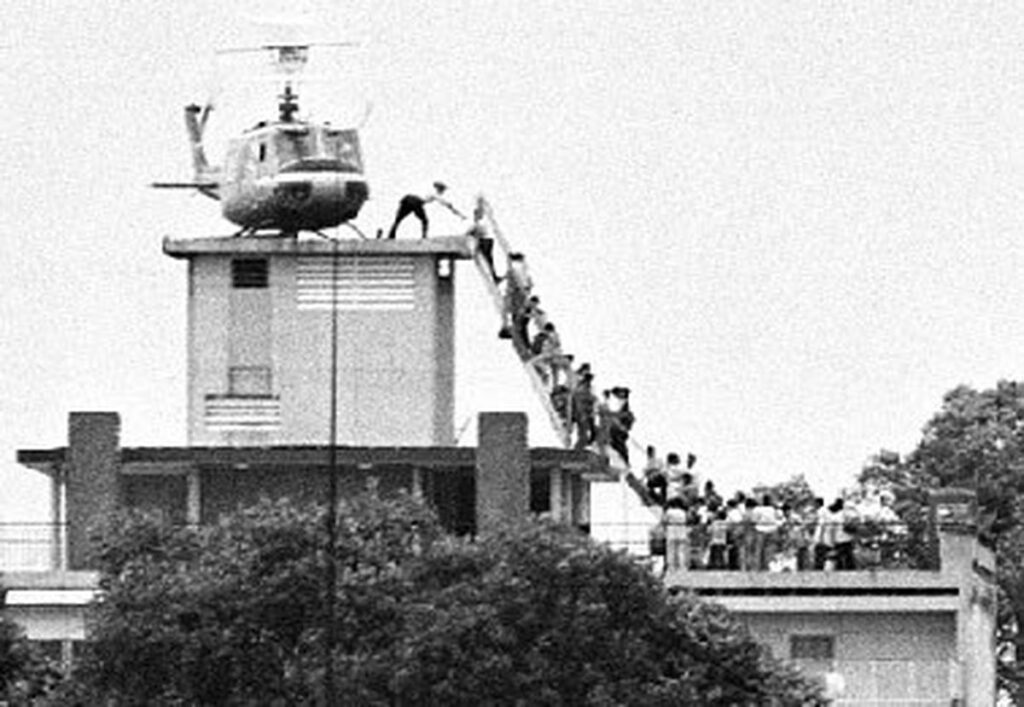

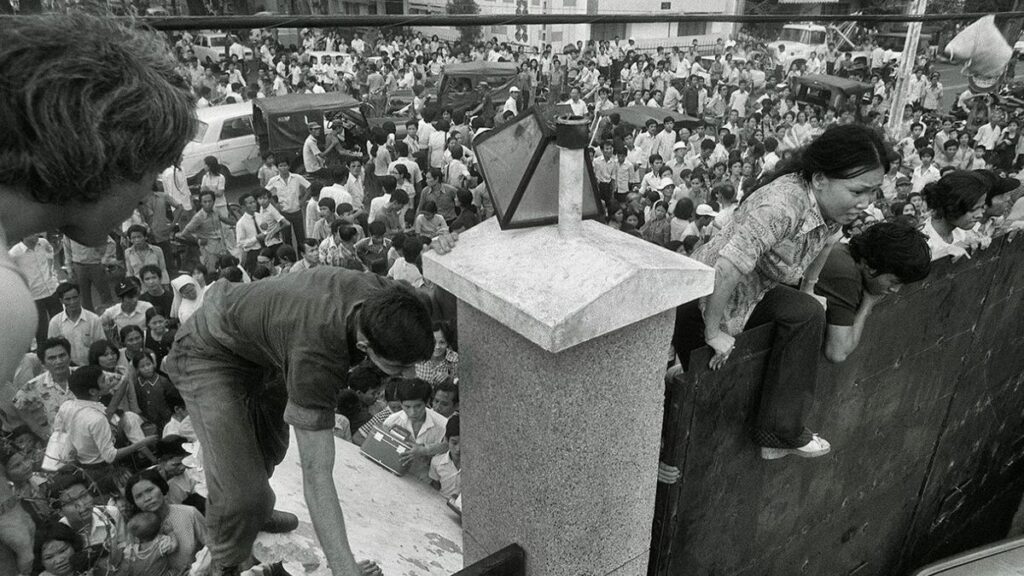

After hundreds of essays and articles and four books, after participating in a couple of documentaries about Vietnam, after years of being a commentator on the radio, years of lectures and public readings—I still wake up in tears on some early dawn, fresh from a vivid dream of a long-lost world. Fifty years, and still some part of me remains that 11-year-old standing alone in the refugee camp in Guam listening to the BBC announcing the fall of Saigon, still mourning a lost country, a robbed childhood.

The old ghosts, I tell you, they hover nearby, not fully exorcised, not fully appeased by the written words, no matter how well turned a phrase.

And how they haunted. My father fought that war from its beginning to end, and through an amazing display of willpower and discipline, got an MBA and became a banking executive in America in his mid-forties. He brought us out of poverty. By all accounts, we were living the American dream, but our nightly ritual at dinnertime always veered back to talk of Vietnam. Over wine or whiskey and soda, he would relive the battles he fought and won. Or else we talked of the people we knew or the lives taken from us, the food we ate, the sound of the street vendors singing in the still, hot afternoon. On some weekends, over drinks, with his war buddies, the battles they fought were relived—bombs fell, helicopters hovered over a battlefield in smoke, and mortar shells exploded. Sometimes there was great laughter over fond memories. Other times their voices were somber, especially when speaking of fallen comrades and those incarcerated in the reeducation camps—voices that filled me with despair.

Our lives in America were thus contradictory. Weddings, college graduations, new homes, European vacations, babies born—the American dreams realized—were peppered with the tragedy of Vietnam, a past that kept bleeding into the present. Our story of ascendency in America was constantly pulled backward to a place robbed, a country gone, a way of life no more.

The war erupted when mother wept, reading flimsy, thin letters sent from relatives and friends in Vietnam those Cold War years—and their stories of destitution and deaths, and their losses, made our evening sober, muted. And even if we didn’t want to have anything to do with it, Vietnam kept showing up on TV and in newspapers in those early years. In the evening news with Walter Cronkite, we saw blurry images of boat people bobbing up and down on their rickety boats, waving flags to a passing ship, begging to be saved. Then the phone rang: Uncle has died from heart failure after his interrogation. The phone rang again: Mrs. so and so and her family had drowned at sea.

Eventually, I came to accept my American optimism will always be burdened by memories of a lost country. The war ended. The war never ends.

And yet, without writing, without that effort to give meaning to it all, I couldn’t imagine how I would have managed after all these years.

So, I write. To rein in the chaos. I write because history, as Baldwin warned, is trapped in people and people are trapped in it, but I write knowing that for all of Baldwin’s warning, there’s always M. Scott Momaday’s wise counsel: “Anything is bearable as long as you can make a story out of it.”

These days, I still strive toward words, though my power wanes and my will weakens. But I write with the knowledge gained from the years that there is transformative power in a well-told story.

Take this episode that continues to give me strength.

A friend taught my short story “Show and Tell,” from my collection Birds of Paradise Lost, at the University of New Orleans to a group of high school students who wanted to be teachers. In the story, a refugee kid enters a seventh grade classroom and the class clown befriends him. Together they face a school bully named Billy, whose father was wounded in Nam. Billy hounds them, calls them names. The Vietnamese boy speaks no English, but he can draw, so he draws pictures of his sufferings during class show-and-tell. Helicopters and soldiers, and a boat on a turbulent sea blooms onto the blackboard, and the refugee boy calls out to his new friend to narrate his story. Together, as a team, they manage to tell a story of grief and travail that causes the class to erupt in applause and cheers.

And here’s the beatific moment: The friend who taught this class shared an email sent to him from one of his students. After having read my story, his student went out and sat in the backyard and wept. He recognized himself in it: He was Billy. Poor and full of family grief, he took it out on the smelly Vietnamese kid who came into his classroom, someone even lower on the totem pole than him. But now, having read my story, something broke; now he was determined to go and find that kid to say, “I’m sorry.”

“Congratulations,” the professor friend wrote. “Your story made the bully cry.”

When I started out all those years ago, I only wanted to give shape to pain. But over the years, I find that there are the unexpected gifts of literature. It connects, and it transforms the lives of others in ways beyond my imagination. If trauma can be inherited, then let the written word, the well-told tale, be the salve, the elixir to heal wounds, the bridge that spans the generations, the vector toward peace. (The Washington Spectator)

At age 11, Andrew Lam left Vietnam with his family two days before Saigon fell; they were among the first wave to resettle in California. He went on to study biochemistry at UC Berkeley but decided to become a writer and journalist instead. Lam is the author of Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora, which won the 2006 PEN Open Book Award, and East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres. Lam was an editor and cofounder of New American Media, an association of over 2,000 ethnic media outlets in America. He was a regular commentator on NPR’s All Things Considered for many years and was the subject of a 2004 PBS documentary, My Journey Home. His essays have appeared in numerous newspapers and magazines, and he wrote a column for The Huffington Post and Shanghai Daily. His short stories have been widely taught and anthologized. Birds of Paradise Lost, his first story collection, won the Josephine Miles literary award and was a finalist for the California Book Award. His latest book, Stories From the Edge of the Sea, was published last month. He is working on a novel.